All the talk of budget deficits really focuses on the wrong deficit. It is the output deficit of goods and services lost because of the Great Recession that is most important, not the state and federal budget deficit(s), since budget deficits will only be paid down with increased tax revenues that come from increased production.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP.org) has been tracking the output deficit since the beginning of the downturn, and it shows that overall production (GDP) has now returned to its 2007 level, hence the end of the recovery cycle we have been discussing. But for significant deficit reduction GDP now has to continue to expand to its potential above $14 trillion.

With the latest congressional compromise, analysts are predicting a higher GDP growth rate in 2011—which if true might boost growth to that $14 trillion plus level. The legislation’s extensions of federal unemployment insurance and Obama-era tax cuts for low-income households (i.e., the 2009 improvements in the Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, and college tuition tax credit) — all policies insisted upon by the White House — are a big reason for the increased estimate.

Economist Mark Zandi of Moody Analytics gave the best analysis of the compromise. “The deal’s surprisingly broad scope meaningfully changes the near-term economic outlook. Real GDP growth in 2011 will be nearly 4 percent, approximately 1 percentage point greater than previously anticipated. Job growth will be more than twice as strong, with payrolls growing by 2.6 million. Unemployment will be more than a percentage point lower; instead of hovering near 10 percent through the year, it will end 2011 well below 9 percent.”

In fact, economic growth has been subpar since 2000, with just 5 million jobs created 2000-08 and another 1 million jobs added since January 2010, after the loss of 8 million jobs during the Great Recession.

Most of the budget shortfall has been due to the lost revenues of the Bush tax cuts during the last decade, with military spending adding another $1 trillion, whereas the output deficit comes mainly from lost jobs—8 million from this recession alone, as we said. So the best revenue enhancer would of course be more robust growth. In fact, if GDP growth exceeded 3.5 percent longer term as it has over the last 75 years (i.e., including the Depression), social security would never be in danger of running out of funds. The current projections are based on a long term forecast 2.6 percent GDP average growth rate, which has never happened.

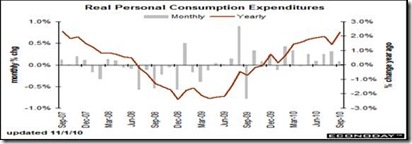

The bottom line is that higher GDP growth increases personal incomes, which began their most recent decline at the beginning of the Great Recession and only started upwards again after it ended in July 2009. Real, after inflation, personal incomes are currently 95.5 percent of the last peak, so demand can’t pick up substantially until consumers’ financial health is restored.

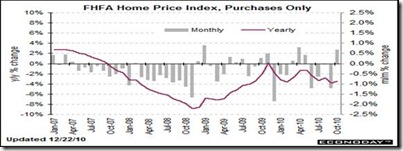

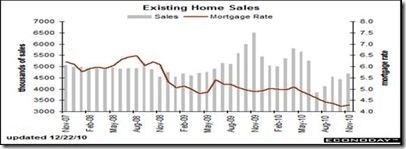

In sum, the best bang for the buck is boosting incomes of the middle and lower classes who were most affected by the Great Recession. Unemployment insurance has been the most effective boost for the 15 million unemployed, followed by the current one year-2 percent income tax cut for all wage and salary earners. Since consumers will no longer be able to rely on massive borrowing from their homes, they will only be able to spend money the old fashioned way, by earning it.

Harlan Green © 2010

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj6d25COL0Au4dSKWUYtFm9iMgKW6tj3M6D_m2tD3DAAJR9tI9C3osxu8YyoPH6JvYMtdTUqpMlstcwgx5bhQvbrVtKnxIi58h5_1PAS8kzHwm2SqyITBnHg7K1j1LRgpwHvfOiA9r7NA/?imgmax=800)