Financial FAQs

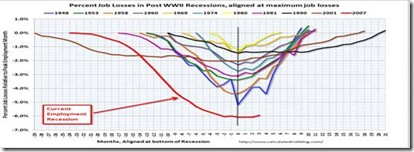

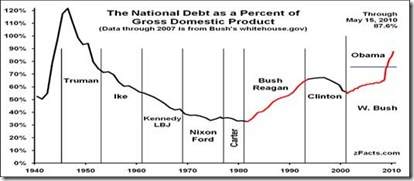

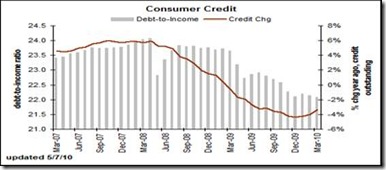

Barron’s columnist Alan Abelson asked just that question this week after the general decline in stocks, and 900 plus point drop in the DOW. Have investors become so cautious because of Europe’s debt problems and the uncertainty of our recovery that they no longer are willing to invest in this recovery? Banks are holding record amounts of deposits because investors are investing little and consumers spending less.

Actually risk comes from the French risqué, to be daring, according to Larousse—so that nothing ‘risqué’ is nothing gained. In fact, the French expression for Dare-devil is Risque-tout (or being totally risqué).

So being risqué is taking a chance in a dare-devil way. Hence periodically wild gyrations in stock prices should come as no surprise—at least to those in for the long haul, like marching towards retirement. Risk = both the potential for gains and losses, but any uncertainty lowers the tolerance for risk.

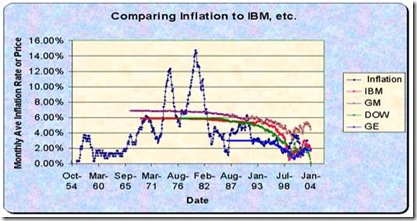

The good news is that stock prices do behave according to certain parameters. One such is inflation. To paraphrase Milton Friedman’s dictum that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, economists generally maintain stock (and bond) prices are always and everywhere inversely related to inflation. Robert Thibadeau is one such economist. His historical graph of stock prices vs. inflation shows that stock prices tend to fall with high inflation, as happened in the 1980s, and rise with low inflation, as happened after 1998.

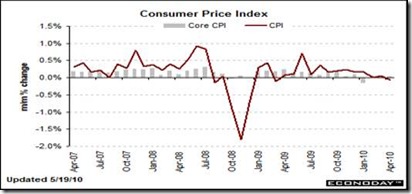

So it is good news that inflation has fallen in past months. Economist Paul Krugman fears it could fall further, however, which might give us something like Japan’s so-called ‘lost decade’ of no growth. But stock prices have been rising in this low inflation environment, which might counteract that tendency to slower growth.

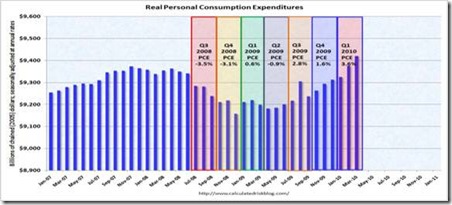

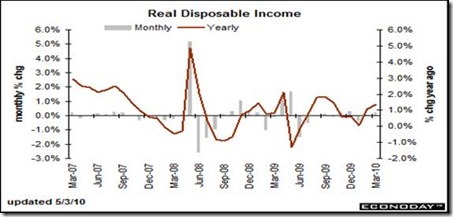

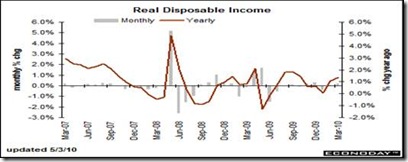

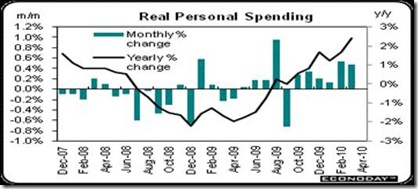

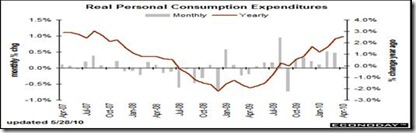

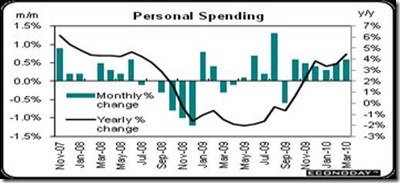

In April, overall CPI inflation dipped 0.1 percent after edging up to 0.1 percent the month before. Core CPI inflation was flat for two months in a row. Year-on-year, overall CPI inflation eased to 2.2 percent (seasonally adjusted) from 2.4 percent in March. The core rate slipped in April to 1.0 percent from 1.2 percent the prior month.  One may argue with the CPI, but the Fed also looks at the Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator, which measures overall prices. And even though year on year, personal income growth for March rose to 3.0 percent, rising from 2.2 percent in February, annual headline PCE inflation in March is 2.0 percent, while annual core PCE inflation was steady at 1.3 percent. This has helped to increase real, after inflation, disposable income.

One may argue with the CPI, but the Fed also looks at the Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator, which measures overall prices. And even though year on year, personal income growth for March rose to 3.0 percent, rising from 2.2 percent in February, annual headline PCE inflation in March is 2.0 percent, while annual core PCE inflation was steady at 1.3 percent. This has helped to increase real, after inflation, disposable income.

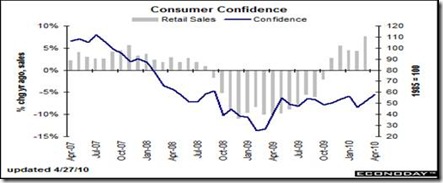

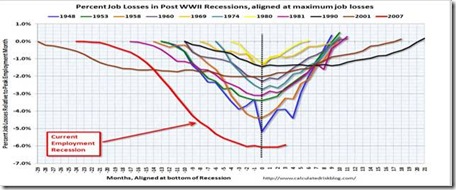

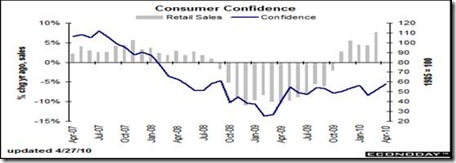

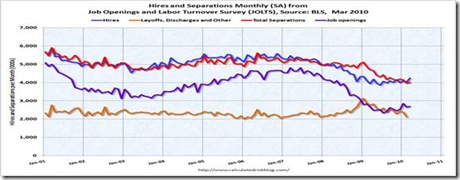

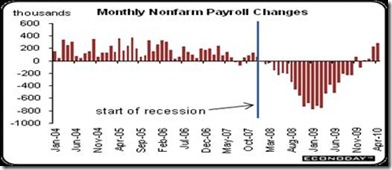

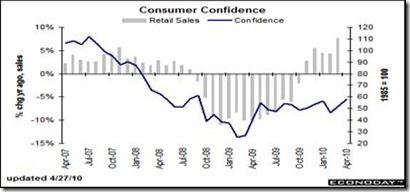

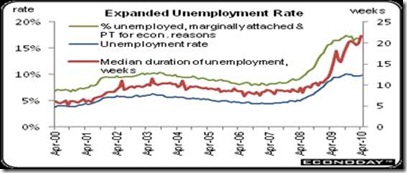

So the combination of lower inflation and higher personal incomes should keep consumers spending and stocks rallying that will prevent a ‘double-dip’ recession. Recessions are always and everywhere a deflationary phenomenon. I.e., prices fall because of a fall in demand, which means a slack economy, which leads to higher unemployment. But why do stocks tend to rally with low inflation? It is a sign that investors appetite for risk is returning, in anticipation of a recovery.

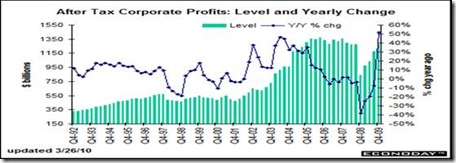

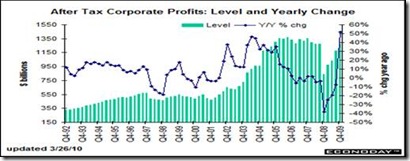

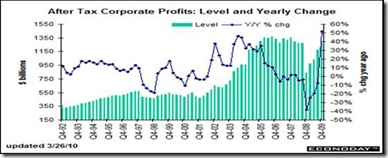

And the latest signs are that investors are again investing and consumers spending. This is the major reason stocks have recovered. And as we reported last week, based on analysts’ 2010 earnings estimate, the ‘forward’ price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 has slipped to 13.7 percent from 15.3 percent less than one month ago, below the historical 100-year average for stock prices—another reason to be daring.

Harlan Green © 2010

| |

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/_MVBAQNWr-nw/S-dAzbZYEvI/AAAAAAAAAEY/OYL5VzanVDI/clip_image004%5B1%5D_thumb%5B3%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/_MVBAQNWr-nw/S-dA0O3YW4I/AAAAAAAAAEg/dzkGFmeE248/clip_image006%5B1%5D_thumb%5B4%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)