Popular Economics Weekly

There really is an innate conflict between policies that create more jobs, and policies that advocate cutting budget deficits during hard times. Policy makers have to ask themselves, which is more important—creating more jobs, or reducing debt? It depends on the timing. Debts are accumulated during bad times—especially public debt—and paid down in good times. The question is when is the economy strong enough to begin to pay down the deficits that have been created.

Everyone knows too much debt was accumulated in the last decade—most from tax cuts; but also from two wars, falling personal incomes, and the last two recessions (2001 and 2007-09). Most of the federal deficits were created by falling revenues that couldn’t cover those higher debt loads incurred by financing tax cuts and wars with borrowed money, as Alan Greenspan has famously said.

So the Wisconsin debate on public employees’ right to collective bargain is bringing this debate front and center—which is a good thing. Most states have to balance their budgets each fiscal year by law. The question is whose budget to cut. Taking collective bargaining (for salaries, not benefits) away from Wisconsin’s public employees is the worst way to balance its budget, because it takes away the means to cure their deficit.

For by reducing salaries and or benefits of its public employees, Wisconsin takes away a huge engine of economic growth by reducing the spending and saving power of its consumers, who as wage and salary earners make up 80 percent of the workforce and 70 percent of all economic activity. The dilemma for policy makers is how to add jobs and keep manageable deficits, in other words.

In fact, the only real way to cure any budget deficit is by growing revenues, not reducing spending. The reason for the deficits (which usually occur during recessions, remember) is loss of tax revenues—whether at the state or national level. This unfortunately is not clear to either most pundits or ideologues. Revenues shrink during recessions, period. And it takes a long time to ‘regrow’ those revenues.

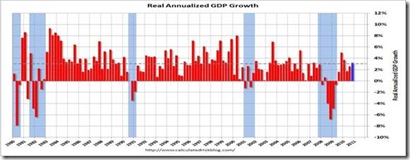

The latest Gross Domestic Product numbers tell us as much. It wasn’t until Q4 2010 just ended that GDP growth—a proxy for overall economic growth—was back up to the level before December 2007, the beginning of the Great Recession. It took all of 2008, 2009, and 3 quarters of 2010, in other words, to return economic growth to pre-recession levels.

(And, it was done with 7 million fewer employed!) Fewer workers are now producing more, so that labor productivity is soaring. But with so-called unit labor costs cut to the bone, productivity—or output per worker—will only decline, unless employers hire more workers.

That is why governments tend to borrow more during hard times, in the hopes that it will stimulate enough spending to stop a precipitous drop in demand, and so jobs. But it is a delicate balancing act, since the credit rating agencies that determine bond interest rates watch budget deficits closely, and will drop a government’s rating almost as quickly as those for corporations.

Collective bargaining is the right of employees to negotiate with their employers, a right that unions in particular have enshrined in their charters. And guess who make up the majority of union membership? Public workers make up 36 percent of public employees, vs. just 9 percent of the workforce in private business. It is a combination of both blue collar (police and firemen), and white collar (teachers and workers in government administration).

So in fact, reducing workers salaries and benefits that make up approximately 80 percent of the workforce in order to cut budget deficits does more than cuts the demand for goods and services. It starves governments of the revenues needed to cure those deficits. Some form of government stimulus spending is therefore necessary until employment returns to levels that create a sustainable demand.

Harlan Green © 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment