Popular Economics Weekly

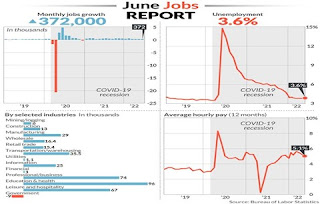

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 372,000 in June, and the unemployment rate remained at 3.6 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Notable job gains occurred in professional and business services, leisure and hospitality, and health care.

I reported last week that weekly initial unemployment claims had been holding at the lowest level since 1970, which was a sign of an extremely tight labor market, and that has proved to be the case.

The unemployment rate held a 3.6 percent for the fourth month in a row. The labor force participation rate, at 62.2 percent, and the employment-population ratio, at 59.9 percent, were little changed over the month. Both measures remain below their February 2020 values (63.4 percent and 61.2 percent, respectively), which means not everyone has gone back to work (1.3 million, actually), and employment rolls still have room to grow.

All sectors showed growth and average hourly wages are still growing at 5.1 percent, a huge increase that will keep consumers spending and the economic growth continuing, despite inflation and rising interest rates.

The Federal Reserve will probably see this jobs number as too hot and continue to raise interest rates, so the debate will continue whether we can return to the Goldilocks era of an economy that is not too hot (inflationary), or too cold (deflationary).

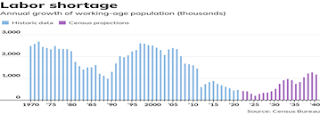

MarketWatch economist Rex Nutting is warning of one obstacle to continued jobs growth, a looming shortage of working-age adults. The baby boomer population bulge of the 1970s has reached retirement age, and the millennials cohort of the 1990s, their offspring, will be approaching retirement age as well, as is seen in his graph of population growth rates.

“But now the tide is going out,” said Nutting. “Next year, the working-age population is expected to grow by just 400,000. In 2024, it’s expected to grow by 300,000 and by just 200,000 in 2025. The pool of workers will begin to grow a bit faster later in the decade and throughout the 2030s, but current projections through 2060 don’t foresee the labor supply returning to the same growth rate we’ve gotten used to over the past 70 years.”

And that means slowing economic growth as well, unless we allow more working-age adults to immigrate and invest in more productive technologies, since more workers producing more goods and services powers economic growth.

How is this a sign of an impending recession? Companies are holding on to their workers for dear life, with one of the lowest unemployment rates in history. The rate was only lower in 1950, dipping to 2.5 percent during the record recovery from World War II.

So now we must worry about the Fed raising interest rates too high and choking off further growth.

Harlan Green © 2022

Follow Harlan Green on Twitter: https://twitter.com/HarlanGreen

No comments:

Post a Comment