Financial FAQs

“With only about a month remaining before its recommendations are due, lawmakers on the congressional supercommittee charged with finding savings from the federal budget wrestled with cuts to defense, foreign aid and other programs on Wednesday”, said Bloomberg Marketwatch.

But the historical record tells us that finding “savings” in government spending will shrink, not expand economic growth. And so finding savings that aren’t spent elsewhere on stimulus programs won’t in fact reduce the federal deficit, which depends on increased growth. So once again as Paul Krugman has said, “And those who are determined to forget the past run a high risk of reliving it — which is why we’re in the state we’re in.”

At the risk of stealing the title from a New York Times Op-ed by economic historian and Rutger’s Professor James Livingston, “It’s Consumer Spending, Stupid”, we now have historical data verifying that consumers and government spending have driven economic growth over the past century, not corporate profits. This should not be surprising given that consumer spending now makes up 70 percent of economic activity.

Professor Livingston’s apostasy is letting us in on the “best kept secret of the last century: private investment—that is, using business profits to increase productivity and ouput—doesn’t actually drive economic growth. Consumer debt and government spending actually do”.

This is blasphemy to the classical orthodoxy, needless to say, but a truth that the #OccupyWallStreet protests recognize. Livingston says, in fact “…corporate profits are…just restless sums of surplus capital, ready to flood speculative markets at home and abroad. In the 1920s, they inflated the stock market bubble, and then caused the Great Crash. Since the Reagan revolution, these superfluous profits have fed corporate mergers and takeovers, driven the dot-com craze, financed the “shadow banking” system of hedge funds and securitized investment vehicles, fueled monetary meltdowns in every hemisphere and inflated the housing bubble.”

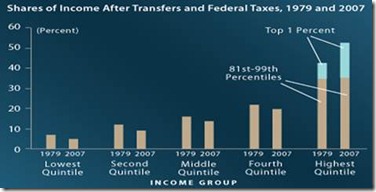

Graph: Congressional Budget Office

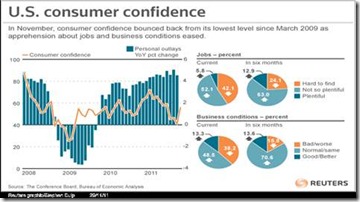

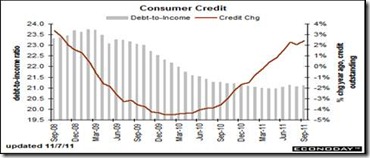

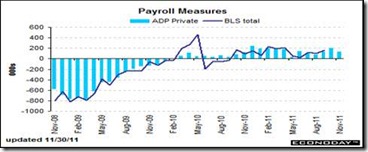

This also tells why this recovery has been so frustratingly anemic. It isn’t consumer debt, as much as the lack of income that has prevented consumers from spending enough to boost economic growth. There has been almost no household income growth above inflation since the 1970s, mainly because so much wealth was siphoned off to the wealthiest via tax loopholes and less progressive tax rates, according to the latest CBO study on income inequality.

It should no longer be a surprise to anyone that the share of income going to higher-income households rose, said the CBO study, while the share going to lower-income households fell. But it’s nice that the CBO is also providing more evidence, to whit:

- The top fifth of the population saw a 10-percentage-point increase in their share of after-tax income.

- Most of that growth went to the top 1 percent of the population.

- All other groups saw their shares decline by 2 to 3 percentage points.

How do we know that it isn’t corporations reinvesting their profits that spurs growth? After all, between 1900 and 2000, real gross domestic product per capita (the output of goods and services per person) grew more than 600 percent.

We know because net business investment declined 70 percent as a share of G.D.P. over that century, says Professor Livingston. In 1900 almost all investment came from the private sector — from companies, not from government — whereas in 2000, most investment was either from government spending (out of tax revenues) or “residential investment,” which means consumer spending on housing, rather than business expenditure on plants, equipment and labor.

In other words, over the course of the last century, net business investment atrophied while G.D.P. per capita increased spectacularly. In other words, corporations decided to spend their profits elsewhere. “The architects of the Reagan revolution tried to reverse these trends as a cure for the stagflation of the 1970s, but couldn’t, said Livingston. In fact, private or business investment kept declining in the ’80s and after. Peter G. Peterson, a former commerce secretary, complained that real growth after 1982 — after President Ronald Reagan cut corporate tax rates — coincided with “by far the weakest net investment effort in our postwar history.”

So even cutting corporate taxes, the cry of conservatives today, hasn’t encouraged corporations to invest in future growth. Professor Livingston has done a great service in what may be a first—actually exploding the myth that profits drive growth. It also explodes the myth that corporations have their customers’ best interests at heart. For their customers are consumers in the main, and consumers’ incomes have not even kept up with inflation. The huge jump in labor productivity has not been shared by their employees, in other words.

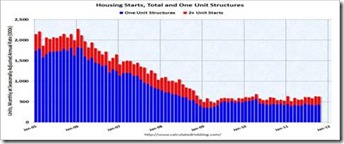

On the other hand, it is the investor class that profited immensely from the myth that business investment creates jobs. Even though the historical record shows it merely bloated the financial sector from 8 percent to more than 20 percent of GDP over the past decade, which led to excessive speculation. It was excessive investments in new technology, for instance, that caused the dot-com bubble and market crash in 2000. Then came the housing bubble that resulted from overbuilding of housing, fuelled by too easy credit conditions.

“Consumer spending is not only the key to economic recovery in the short term; it’s also necessary for balanced growth in the long term,” says Professor Livingston. “If our goal is to repair our damaged economy, we should bank on consumer culture — and that entails a redistribution of income away from profits toward wages, enabled by tax policy and enforced by government spending. (The increased trade deficit that might result should not deter us, since a large portion of manufactured imports come from American-owned multinational corporations that operate overseas.)”.

We don’t need the traders and the C.E.O.’s and the analysts — the 1 percent — to collect and manage our savings. Instead, we consumers need to save less and spend more in the name of a better future. We don’t need to silence the ant, but we’d better start listening to the grasshopper, says Professor Livingston.

So when will consumers—you and I, that is—wake up to the fact that the future is ours for the taking?

Harlan Green © 2011